ALBUM // Empty Country – Empty Country

Post by Tommy

In one of the most surprising moments of Empty Country’s eponymous debut album, a character (“Becca”) pulls an all nighter making fake eclipse shades to trick unwitting people into staring directly at the sun. “Feeling for the light switch,” the narrator concludes, “They will hear the ocean.” Offering little in the way of motive, the song becomes something of a math equation: robbed of their sight, they are filled with the sound of nature.

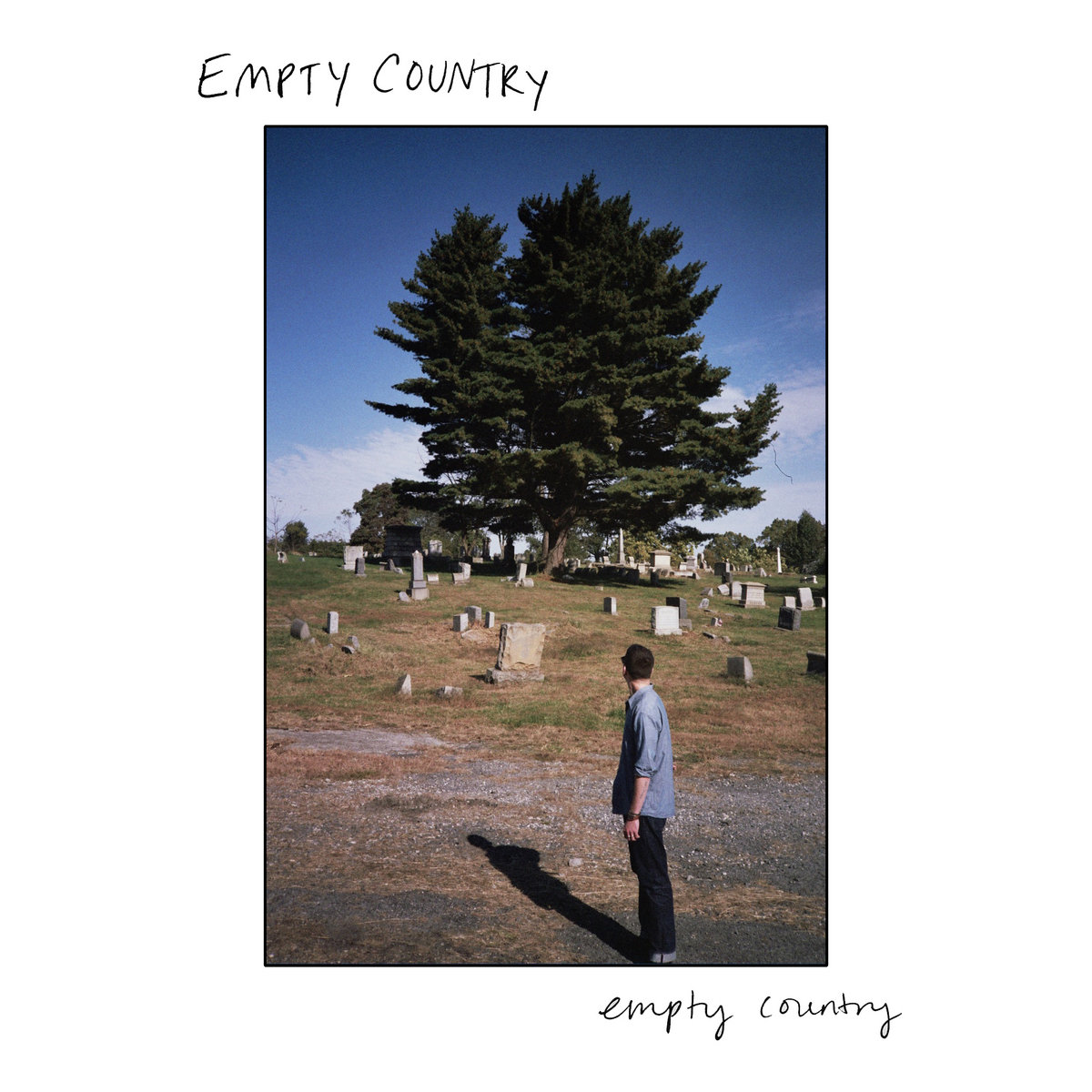

Despite a series of trials and delays, D’Agostino’s songwriting masterwork has arrived in a moment the real world, isolated and insular, mimics strangely the album’s own blurred and dusty vision of the country. The album’s narrators and protagonists, dodging between apparent lived experience and invented characters, frequently see themselves as simply a hole in the rest of the world, a shadow against the trees, the desert, the rocks, even the people. The opening track “Marian” (which sounds in moments like Tom Petty covering something off Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska) is a tender and grim story of a clairvoyant Virginian who foresees their own imminent death in a mine collapse as they bring a daughter into the world, and sees in “arcing streams” how the child will live without them (“Hole for a heart / From the start,” they repeat). The song begins with them using the knowledge of their impending (but later) death to justify driving drunk and recklessly — the song teeters on the edge of defeatism, the narrator failing to question their fate and frequently bemoaning the way it will shortchange their family. It’s an image of a life traced in its own absence. As the next track’s narrator more succinctly illustrates it, as the music breathes and tightens around their voice: “I’m more than my thoughts… I leave a me-shaped tunnel in the tawny fog.”

The characters across Empty Country’s ten tracks agonize and pine for the world moving around them, often seeing it only as it reflects or refracts through other things (like the narrator of “Emerald” who watches the eclipse for the shadows, or memories seen through a video camera in “Chance”). The album is nothing if not true to its name here, full of wide, cinematic arrangements which illustrate a world in sometimes quiet, sometimes triumphant deference to its narrators, lonely, scared, and considering ways to pull the world inside them. “Becca,” by design or by accident, presents a false barrier which brings the natural world inside her victims. The narrator of “Untitled” takes LSD because they “like the way it makes trees breath (sp) and way / Just like they always have,” trying to alter their own perception just to see something in nature they nonetheless feel has always been there — maybe just trying to evoke it more vividly. In “Ultrasound,” the narrator waiting on the results of a cancer check, agonizing: “A universe expands inside us / Body horror.” The narrator of “Chance” echoes this image but in the affirmative: “Making someone out of nothing / We gave our own secret name / To this painted world.”

The lyrics to “Chance” seem to possibly evoke a pregnancy as an internal growth, while “Ultrasound” deals with the much more terrifying growth of a potential cancer even in the same terms, each imbuing the growth with a cosmic significance. In the scarier portrayal, the universe “expands” with the cancer, an extension of its form outside the body — a terrifying intrusion or even overgrowth of the world into it. In the calmer “Chance” the universe that grows with the baby is a new one that’s merely a facsimile of the world outside, grown in isolation and known only to the narrator and (we assume) their partner who can identify it by its “secret name.” The anxiety of “Ultrasound” is measured relative to the awful whim of the natural universe. In “Chance,” calm is found in ways the narrator finds to make that entropy slow, as they say— reliving memories through a video camera, singing old songs, insulating the world and their life from the random. All this is set to a lullaby, presented serenely and safely, even as whispers and artifacts of something noisier creep through the mix.

The album’s closer, “SWIM,” (an online acronym for “Someone Who Isn’t Me,”) is the fragmented memoir of a “blue eyed sociopath” admitting the pain they may have caused in a blacked-out haze and even approaching a moral breakthrough before committing to an excuse: “We’re evil, baby / sorry / I guess some people have to be.” The deferral evokes the title track, again, of Nebraska, in which a death row inmate asked to explain a killing spree simply posits “Sir, I guess there’s just a meanness in this world.” In both songs the narrator identifies themself as nothing more than a factor of nature’s cruelty. And yet, the hook of “SWIM,” sickly sweet and nearly out of a mattress commercial jingle, is a tender and vulnerable plea: “Maybe you could come and live it down with me.” This person, lonely and lost, pleads sweetly for connection while refusing to reckon with damage caused to others and committing to an identifier that robs them of their capacity for empathy — keeping people out while begging them to come in.

The population of Empty Country are so often distrustful of the world, and struggle to break and sometimes even recognize the barriers they themselves have erected to keep the outside world out. They don’t always fail — relief dyes the end of “Ultrasound,” for instance, when the narrator finds faith in the world enough to suspend their worry and go outside (“Realized / The million things that all went right … Let’s leave this house / Let’s take a ride”) — but even then, the song begins with the couple turning to nature to try to relax and finding themselves unable to. The parent of “Marian,” on the other hand, submits to the whim of the world and loses connection with their family, just as “SWIM,” in identifying with the evil order of nature, ends up isolated and lonely.

The songwriting and arrangements here, enlivening the extremes of ease and frenzy that D’Agostino previously explored in his band Cymbals Eat Guitars, adamantly refuse to comment or make judgement or excuses for the characters. The resulting portrait is an honest and complicated one of the agony and ecstasy of our attempts to commune with the world around us, particularly in an increasingly inward and defiant modern existence. Some people look to others to escape the terrifying possibilities of the natural world; others use those same possibilities as an excuse to ignore the people around them.

Right now, the country feels as empty as it ever has in most of our lifetimes, even as we know definitively that we are here, at home. So when it’s empty — is it empty of us, or are we empty of it?

Empty Country is out now on Get Better Records. Buy it here.